"The story of a little girl, Jihad, facing discrimination because of the name her parents gave her.

Pierce the veil--Unlock the truth--Racism, Nationalism, & Islamophobia, examined through the unbiased lens of scientific inquiry."

The Qur'an reports three interesting statements about the Pharaoh and his gods. Firstly, when Prophet Moses calls Pharaoh to worship one true God, the call is rejected. Instead, Pharaoh collects his men and proclaims that he is their Lord, most high.

[Qur'an 79:15-24]

Secondly, when Moses goes to Pharaoh with clear signs, they are rejected as being "fake". Pharaoh then addresses his chiefs:

Pharaoh said: "O Chiefs! no god do I know for you but myself...

SURAH 28 , VERSE 38

The last statement comes in connection with the victory of Prophet Moses over the magicians of Egypt. Here the chiefs of Pharaoh say to him that this victory of Moses over the magicians could result in an abandonment of you (i.e., Pharaoh) and your gods (Arabic: wa yadaraka wa ālihataka) in favour of the God of Moses.

And the chiefs of Pharaoh's people said: "Do you leave Musa and his people to make mischief in the land and to forsake you and your gods?" He said: "We will slay their sons and spare their women, and surely we are masters over them."

SURAH 7 , VERSE 127

This verse refers to other gods in Egypt who were Pharaoh's gods. In other words, a distinction is made between Pharaoh and his gods.

However, according to Christian missionaries, the statement reported in the Qur'an 28:38 is in "direct contradiction" to Qur'an 7:127.

"In other words, the Pharaoh claims that he is the only god for his people, the Egyptians, in direct contradiction to 7:127 where the chiefs of his people express concern that Moses' victory could lead to the downfall of their traditional Egyptian gods (in the plural)."

And:

"This is an enormous historical error. The Pharaohs believed themselves divine, however there is no evidence that any Pharaoh considered himself the one and only god. Amenhotep is considered to be a monotheist, however he did not hold himself to be the one and only god, he believed that title belonged to the god Aten [also called Aton]. The god Ra was considered the highest god in ancient Egypt, not the Pharaoh."

In order to support their claim of "direct contradiction", they quote Muhammad Asad, a well-known Qur'an translator, who considers that the Qur'an 28:38 should not be "taken literally" as the Egyptians also worshipped many gods. Given the fact that Asad is better known for his translation of the Qur'an rather than his scholarship in the religion of ancient Egypt, the missionaries then go on to explain the alleged "discrepancy" without any recourse to reliable, verifiable historical sources. As one navigates the jumbled maze of verbiage, one encounters apparently innocuous questions such as:

Did the Egyptians have many gods or only one god? Since this may not have been the same at all times, we would have to ask more specifically: What was the religion of the Egyptians at the time of the Exodus?

Who was Pharaoh and was he considered divine, human or both? What was his relationship with other gods of Egypt? Whom did the Egyptians consider as their principal god? In order to answer questions like these, we will examine a selection of primary and secondary sources. However, at the outset, it must be said that since the setting of the story of Moses in both the Qur'an and in the Bible is in the New Kingdom Period, more specifically, according to majority of the biblical scholars, during the time of Ramesses II or Merneptah, all our examples of the nature of ancient Egyptian religion would come from this period.

In order to understand this distinction between Pharaoh as god of Egypt and his gods, let us delve briefly into the nature of ancient Egyptian religion. We will only provide a general description here and readers may refer to the cited works.

It is well-known that the Pharaohs have often been characterized as gods on earth. While the kingship as an institution may have continued fairly constantly throughout more than 3,000 years, just what the office signified, how the kings understood their role, and how the general populace perceived the king do not constitute a uniform concept that span the centuries without change. In other words, the ancient Egyptians' view of the king, implied by various historical references, was not static. It underwent many changes.[2] From the early times the epithet nṭr referred directly to the king as a god. Sometimes the term occurred alone and at other times it appeared with a modifying or descriptive word.

Tradition says that in the beginning, kingship came to the earth in the person of the god-king, Rēʿ,, who brought his daughter, Maat, the embodiment of Truth and Justice, with him.[4] Therefore, the beginning of the earth was simultaneous with the beginning of kingship and social order. The king ruled by divine right, his office having come into existence at the time of the creation itself.

The kings of Egypt legitimised their claim to the throne in ways that were influenced by religious beliefs. The god-king, Horus, was the son of Osiris who had been king; and so every new king of Egypt became Horus to his predecessor's Osiris. By acting as Horus had towards Osiris, in other words, by burying his predecessor, each new king made legal claim to the throne. The divinity was only acquired through the rites of ascension to the throne of Egypt. The device of theogamy was used for this purpose. Here, the principal god of the time was said to have assumed the form of the reigning king in order to beget a child on his queen: that child later claimed to be the offspring of both his earthly and heavenly father; and the earthly father was quite content to be cuckolded by the god.

Ancient Egyptians were aware of their monarch's inherent mortality. The unavoidable question now arises: How could they rationalize this apparent human/divine dichotomy of their rulers? It could be that it was not a conflict for them. The king seemed to possess human aspects at times and divinity at others. The Egyptians knew that he originated in the world of humans, but he could function in both worlds. A ruler envisioned as both human and divine was best suited to intercede between the human and divine worlds. Not surprisingly, due to this perceived fluidity of the king's nature, it was not difficult for Egyptians to develop variations on and additions to their concept of kingship. The king's human/divine dichotomy was a unifying factor in Egyptian religious life. In theory, he was chief priest in every temple; the only person entitled to officiate in the temple rituals; the only person entitled to enter the holy of holies within the temple. Obviously, the king could not be in every temple at once. However, the fiction was always maintained in the reliefs carved on the walls of temples, which always show the king making offerings to the gods. He was the embodiment of the connection between the world of men and the world of gods. It was his task to make the world go on functioning; it was his task to make the sun rise and set, the Nile to flood and ebb, the grain to grow: all of which could only be achieved by the performance of the proper rituals within the temples.

By the early New Kingdom, deification of the living king had become an established practice, and the living king could himself be worshipped and supplicated for aid as a god.

During the time of Ramesses II, the deification of Pharaoh reached its peak.

God says that Pharaoh addressed his chiefs by saying that he knows for them of no god but himself [Qur'an 28:38]. This statement can be verified by simply checking the views of the king's subjects, i.e., court officials and the common folk. What the subjects of the Pharaoh could expect of the ruler is very well summed up in a quotation from the tomb autobiography of the famous vizier Rekhmereʿ of Tuthmosis III from 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom Period.

Rekhmereʿ affirms that the officials in ancient Egypt considered Pharaoh to be their principal god, thus indirectly confirming the statement in the Qur'an that he knew of no god for them but himself. Furthermore, Rekhmereʿ adds that the ruler had divine qualities such as omniscience and a wonderful creator.

Furthermore, the king was recognized as the successor of the sun-god Rēʿ, and this view was so prevalent that comparisons between the sun and king unavoidably possessed theological overtones. The king's accession was timed for sunrise. Hence the vizier Rekhmereʿ explained the closeness of his association with the king in the following words:

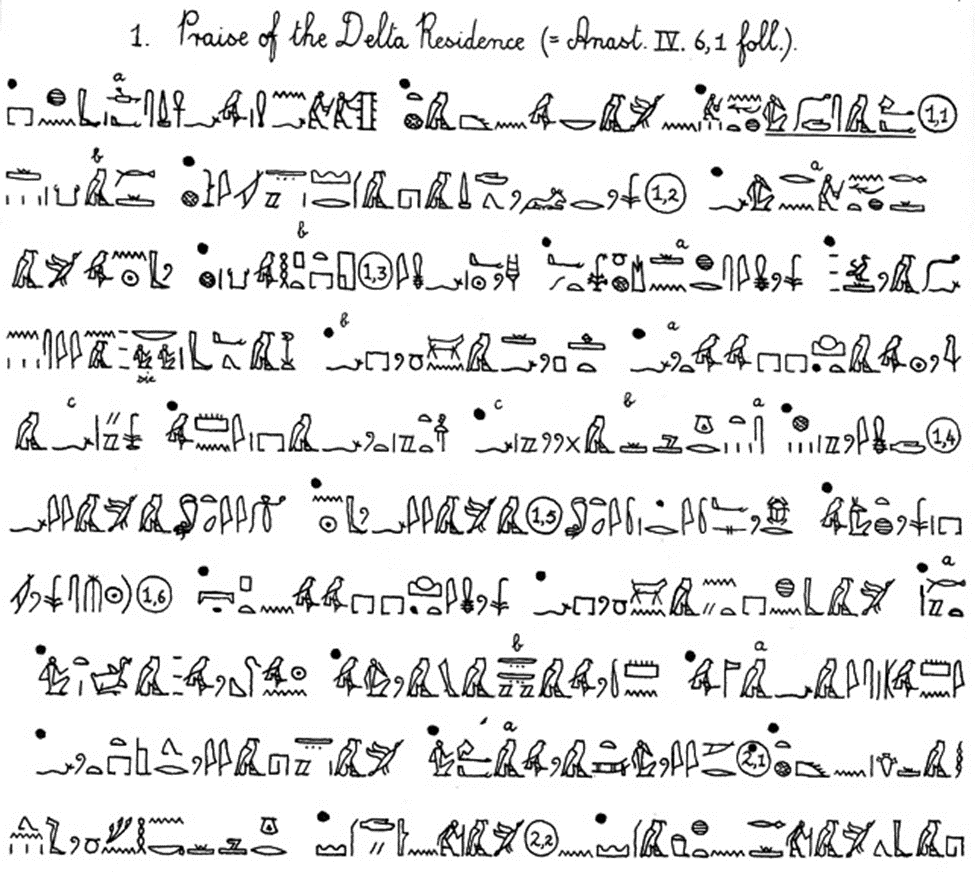

Rekhmereʿ also adds that the whole of Egypt followed the ruler of Egypt, whether chieftains or common folk. Now what about the views of the common folk? For this let us turn our attention to Papyrus Anastasi II dated to the time of Merneptah, successor of Ramesses II. Papyrus Anastasi II begins by "Praise of the Delta Residence" of the Ramesside kings. The textual content of this section is similar to that of Papyrus Anastasi IV, (6,1-6,10).

Here we see Ramesses II in four different aspects, viz. as god, herald, vizier and mayor.

Papyrus Anastasi III is dated to the time of Ramesses II. In the section "Report on the Delta Residence", this payrus describes the beautiful environs of the city of Pi-Ramesses. The description has come down to us in a letter from a scribe called Pbēs to his master Amenemope, in which he describes how he reached the capital and how he found it in extremely good condition. He then speaks about the antiquity of the town, how its ponds were filled with fish and its pools covered with birds, and its meadows verdant with herbage. But most important:

... The youths of Great-of-Victories are in festal attire every day; sweet moringa-oil is upon their heads, (3,3) (they) having the hair braided anew. They stand beside their doors, their hands bowed down with foliage and greenery of Pi-Hathor (3,4) and flax of the P3-hr- waters on the day of the entry of Usimare-setpenre (l.p.h), Mont-in-the-Two-Lands, on the morning of the feast of Khoiakh, (3,5) every man being like his fellow in uttering his petitions.... Dwell, be happy and stride freely about without stirring thence, Usimare-setpenre (l.p.h), Mont-in-the-Two-Lands, Ramesse-miamum (3,9) (l.p.h), the God.

Ramesses II is called the god by the scribe Pbēs, again affirming the fact that even the common folk treated the king as divinity.

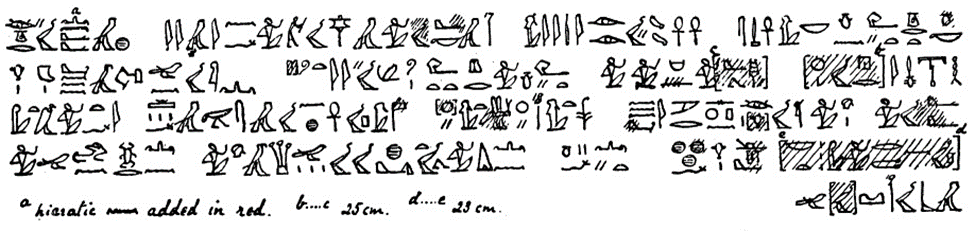

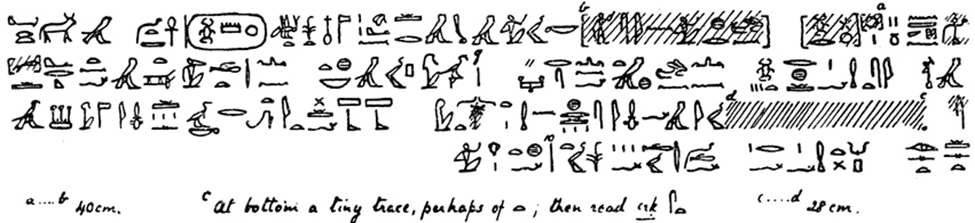

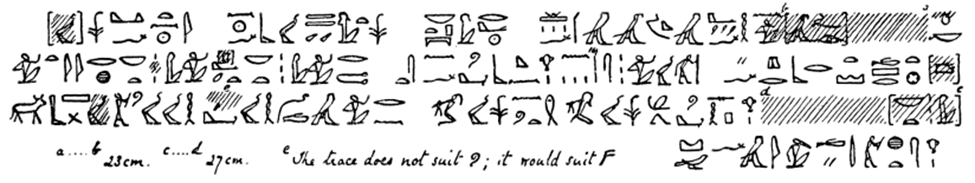

So, how did the Pharaohs view themselves? This is best answered in the hieroglyphs. The rulers of Egypt were not themselves responsible for construction of temples, obelisks, etc. where the inscriptions were engraved; rather, they had a team of architects. The hieroglyphs as shown earlier here give good information about the Pharaoh, his family, his cult and his courtiers.

The Pharaoh exalted himself as Lord, something that cannot be underestimated. It was the way in which ordinary Egyptians understood the residence of their gods on earth.

The basis of ancient Egyptian religion was not belief but cult, particularly the local cult which meant more to the inhabitants of a particular place. Consequently, many deities flourished simultaneously and people were ever-ready to adopt a new god or to change their views about the old. It has been estimated that over 2,000 gods and goddesses were attested in more than 3,000 years of Egyptian civilization. It is well-recognized that not all the gods were worshipped simultaneously, and over the course of Egyptian history one can observe the rise and decline of individual deities. Only a handful of deities from among the 2,000 or so had dedicated temples and priestly offerings. The official state religion of Egypt concerned itself with promoting the well-being of the gods, which they reciprocated by maintaining the established order of the world. The vehicle through which the gods received favour, and in turn dispensed it, was the king, who was, in theory, the chief priest in every temple, aided by a hierarchy of priests. Thus the king was the unifying factor in Egyptian religious life.

The kings of ancient Egypt adopted a very business-like, quid pro quo approach, towards the gods, as seen in the texts carved on the walls of their temples.

If they [i.e., gods] do not obey him, they will have neither food nor offerings. But the king takes one precaution. It is not he himself, as an individual, who speaks, but the divine power: "It is not I who say this to you, the gods, it is the Magic who speaks".

When the Pharaoh completes his climb, magic at his feet "The sky trembles", he asserts, "the earth shivers before me, for I am a magician, I possess magic". It is also he who installs the gods on their thrones, thus proving that the cosmos recognises his omnipotence.

In other words, if the gods did not reciprocate to the offerings of the king, they get demoted in status and standing. Conversely, those gods who do reciprocate in kind are exalted and worshipped. Thus, the gods of Egypt were not truly independent gods; rather they were Pharaoh's gods. Their rise or decline was dependent upon the ruler of Egypt. There are numerous examples from ancient Egypt showing the rise and decline of gods, such as Monthu, Amun, Aten[25], Atenism, Rēʿ, and Ptah.

Since the deification of the living king reached its zenith during the time of Ramesses II, this exalted status resulted in him labelling his monuments with dedications illustrating his divine status such as "Ptah of Ramesses", "Amun of Ramesses", "Rēʿof Ramesses" among others at various temples. As Professor Kitchen:

In Nubia, some time after the completion of Abu Simbel, the "Temple of Ramesses II in the Domain of Re" was cut in the rock at Derr, further downstream on an important bend in the Nile. Later still, the Viceroy Setau had to construct two other temples to match it - one similarly related to Amun (at Wady es-Sebua) and one to Ptah (Gerf Hussein). In these three, therefore, Amun, Re, and Ptah, the gods of Empire were ostensibly worshipped - but (as at Abu Simbel) the actual barque-image in the sanctuary was in fact that of the deified Ramesses II, as a form of Re, as "Amun of Ramesses", and as "Ptah of Ramesses". Such temples, therefore, were almost additional 'memorial-temples' of the king. Not only Amun, Re and Ptah, but also other gods (Seth, Herishef, etc.) were gods "of Ramesses", - and even goddesses: Udjo, Hathor, Nephthys, and Anath from Canaan.

In summary, the gods belonged to Pharaoh - they were his gods.

"The story of a little girl, Jihad, facing discrimination because of the name her parents gave her.

Pierce the veil--Unlock the truth--Racism, Nationalism, & Islamophobia, examined through the unbiased lens of scientific inquiry."