"The story of a little girl, Jihad, facing discrimination because of the name her parents gave her.

Pierce the veil--Unlock the truth--Racism, Nationalism, & Islamophobia, examined through the unbiased lens of scientific inquiry."

Pharaoh said: "O Chiefs! no god do I know for you but myself: therefore, O Haman! light me a (kiln to bake bricks) out of clay, and build me a lofty palace (Arabic: sarhan, lofty tower or palace), that I may mount up to the god of Moses: but as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!"

SURAH 28 , VERSE 38

Pharaoh said: "O Haman! Build me a lofty palace, that I may attain the ways and means - The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens, and that I may mount up to the god of Moses: But as far as I am concerned, I think (Moses) is a liar!"

SURAH 40 , VERSE 36-37

Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie in his book Religious Life In Ancient Egypt says:

The desire to ascend to the gods in the sky was expressed by wanting the ladder to go up.... When the Osiris worship came to Egypt, the desire for the future was to be accepted as a subject in the kingdom of Osiris. When the Ra worship arrived, the wish was to join the company of the gods who formed the retinue of Ra in his great vessel in the sky.

The idea of the Pharaoh climbing a tower or staircase to reach the God of Moses, as mentioned in the Qur’an, is in consonance with the mythology of ancient Egypt.

Standing before the gods, the Pharaoh shows his authority. He orders them to construct a staircase so that he may climb to the sky. If they do not obey him, they will have neither food nor offerings. But the king takes one precaution. It is not he himself, as an individual, who speaks, but the divine power: "It is not I who say this to you, the gods, it is the Magic who speaks".

When the Pharaoh completes his climb, magic at his feet "The sky trembles", he asserts, "the earth shivers before me, for I am a magician, I possess magic". It is also he who installs the gods on their thrones, thus proving that the cosmos recognizes his omnipotence.

We are in no way suggesting it was only in ancient Egypt this belief was held, as Egyptologist I. E. S. Edwards correctly points out:

The Egyptians were not the only ancient people of the Middle East who believed that the heaven and the gods might be reached by ascending a high building; a kindred trend of thought prevailed in Mesopotamia. At the centre of any city in Assyria or Babylonia lay a sacred area occupied by the temple complex and a royal palace.

It is clear now that the idea of the Pharaoh ascending to the sky exists independently and has no connection with the biblical story of the “Tower of Babel”, which is believed to be a ziggurat.[155] The singular use and insistence on the “Tower of Babel” as a source of this particular Qur’anic statement appears to be a convenient device for those wishing to explain the Qur’an's supposed dependence on biblical material, and a lack of interest on their part in widening the historical investigation. Having said this, it must be added that the issue of Pharaoh climbing up a high tower depicted in Qur’an 28:38 has attracted the attention of Father Jacques Jomier, a Catholic scholar and missionary. Jomier asks:

Here Pharaoh... asks Haman to build him a high tower so that he can ascend to the God of Moses (cf. v. 36). Could this be a vague recollection of the pyramids?

The answer is uncertain. Some of the Egyptian pyramids were indeed tall structures. If the Pharaoh did ask for a pyramid then it was as if he was asking Haman to build his tomb! And if that was indeed the case, then the Pharaoh has proven himself to be a mortal and not the God he had claimed to be.

Jomier’s suggested connection between the pyramids and the tower in the Qur’an brings us to a related but important issue. If Pharaoh, a god of ancient Egypt, addressed other gods by climbing up a staircase or a high building, what would happen when the ruler of Egypt died? How did he meet with other gods? Did he ascend to them? If yes, what was the instrument of his ascension? To understand this, let us turn our attention to some interesting evidence dealing with the pyramids and the royal tombs. There is a copious amount which can be seen in funerary rituals and spells first inscribed on the sarcophagi and the subterranean walls of nine Old Kingdom pyramids.[158]

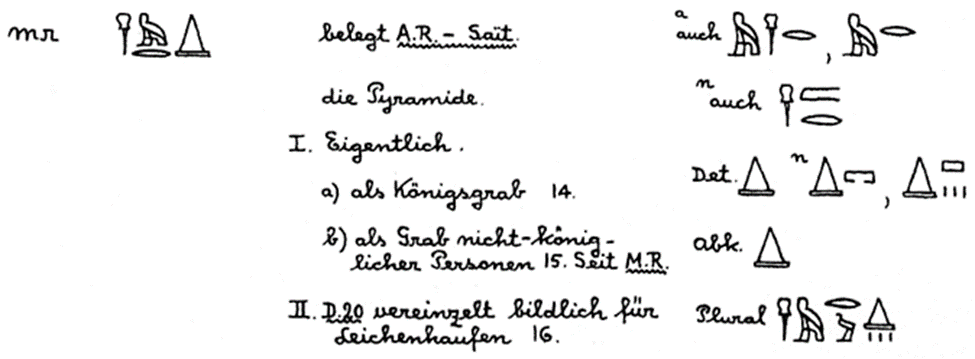

What was the function of the pyramid? The primary function was to house the body of a dead King, his ka or spirit, and his funerary equipment for use in the next world. It was a royal burial site. The pyramid tomb served as a place on earth where food and drink could be brought regularly to supply the need of the ka. The word ‘pyramid’ probably derived from Greek pyramis. The Egyptians themselves used the word ‘M(e)r’ to describe pyramids, and it has tentatively been translated as a ‘place of ascension’. Verner says:

The shape of the pyramid has most often been interpreted as a stylized primeval hill and, at the same time, a gigantic stairway to heaven. In fact, the Egyptian terms for "pyramid" (mr) has been derived from a root i`i ("to ascend"), thus giving "place of ascent."

Similarly, Lehner points out:

The word for pyramid in ancient Egyptian is mer. There seems to be no cosmic significance in the term itself. I. E. S. Edwards, the great pyramid authority, attempted to find a derivation from m, 'instrument' or 'place', plus ar, 'ascension', as 'place of ascension'. Although he himself doubted this derivation, the pyramid was indeed a place or instrument of ascension for the king after death.

Not surprisingly, the Egyptian word ‘M(e)r’ has the determinative showing a triangle with a base to represent the pyramid (Figs. 4 and 5).

After death, the king would pass from the earth to the heaven, to take his place amongst the gods and to join the retinue of the sun-god. However, he needed a way to reach the sky from the earth, a bridge slung between this world and the next, a “Place of Ascension” – a pyramid. The Pyramid Texts inscribed on the sarcophagi and the subterranean walls served as “instructions” for this ascension.

Taking into consideration the fact that so far the Qur’anic story relating to Pharaoh and Haman can be well-supported from the point of view of an ancient Egyptian setting, let us now consider the person Haman, a leading supporter of the Pharaoh. Should ‘Haman’ be understood as a personal name or as a title, similar to the Qur’anic usage of the title ‘Pharaoh’? Further, could Arabic Haman be a curtailed form of an ancient Egyptian name or title? Writing in the Encyclopaedia Of The Qur’an, A. H. Johns wondered if Arabic Haman could be an Arabized echo of the Egyptian Ha-Amen, the title of the Egyptian High Priest, second in rank to Pharaoh.[163] He does not provide any evidence, however. Nevertheless, these interesting suggestions raise a number of interrelated points on a linguistic, historical and religious level and require a thorough investigation before reaching a judgement. Broadly speaking, there are two lines of enquiry that open in front of us, i.e., Haman as

A further subset of these two lines of enquiry may also be included if the name or title, whether curtailed or not, is Arabized or simply an ancient Egyptian name. The search for Haman of the Qur’an in ancient Egypt must take into consideration the evidence from the Qur’an itself. We know the following from the Qur’an concerning the person Haman:

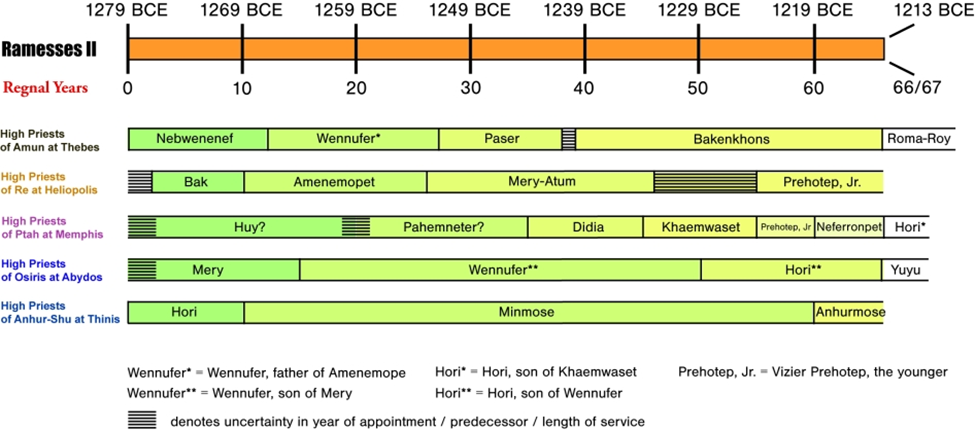

Taking into consideration these three important points, the question now arises as to which period of ancient Egypt we should search for the Haman mentioned in the Qur’an. Our earlier study on the identification of Pharaoh during the time of Moses suggested that it was the time period associated with Ramesses II. So, we have narrowed almost c. 3000 years of ancient Egyptian history to a specific timescale, i.e., to the reign of Ramesses II from 1279-1213 BCE, which is ~66 years, for the setting of the Qur’anic story of Moses involving Haman.

I. Haman As A Title Of A Person In Ancient Egypt: Western scholarship writing favors Haman as a personal name. This derives from their understanding of the alleged connection between the Qur’anic and biblical Hamans. However, we have shown Qur’anic Haman in his ancient Egyptian context by examining various elements of the Qur’anic story from a historical point of view. In turn, this opens up another line of enquiry, i.e., viewing Haman as a title of a person. Such an undertaking is also supported by the fact that, in the Qur’an, the king who ruled during the time of Moses is repeatedly called “Pharaoh” (Arabic, firʿawn). This comes from the ancient Egyptian word "per-aa", meaning, in the Old Kingdom Period, “King's palace”, “the great house”, or denoting the king’s large house. However, in the New Kingdom Period, it was the title used to refer to the king of Egypt. Could the usage of ‘Haman’ in the Qur’an be similar to that of ‘Pharaoh’, i.e., an Arabized version of an ancient Egyptian title? Such a question can be approached by looking into various lexicons dealing with ancient Egyptian names, whether of gods or persons, and how these names came to be used in a variety of different contexts.

One may be tempted to say that the nearest equivalent of Qur’anic Haman (= HMN, in Arabic) in ancient Egyptian is either HMN or ḤMN in the consonantal form. However, this assumes that the consonants in Arabic and ancient Egyptian were pronounced in a similar way and that the ancient Egyptian name was not Arabized. Such a straight forward one-to-one correspondence of the consonants from ancient Egyptian to Arabic is weakened by the fact that the phonology of ancient Egyptian (a dead language!) is still an ongoing study[164] and the evidence for Arabization of ancient Egyptian names exist in the Qur’an. Nevertheless, there is an argument to be made for ḤMN in ancient Egypt being used in the title for a priest in a temple associated with the deity ḤMN itself. This leaves us a tantalizing clue that an ancient Egyptian priest of a specific deity’s temple could have that deity’s name in his title.

During the time of Ramesses II, the ancient Egyptian deity ’IMN or Amun, as it is called in the literature (Amun is the Coptic articulation of ancient Egyptian ’IMN), reigned supreme and had a large, dedicated temple in Karnak. Kitchen says:

The great gods of the state stood at the head of Egypt and of the pantheon, as patrons of Pharaoh. Most renowned was Amun, god of the air and of the hidden powers of generation (fertility and virility), home in Thebes. As god of Empire, he was giver of victory to the warrior pharaohs... To him [i.e., Amun] belonged all the greatest temples of Thebes.

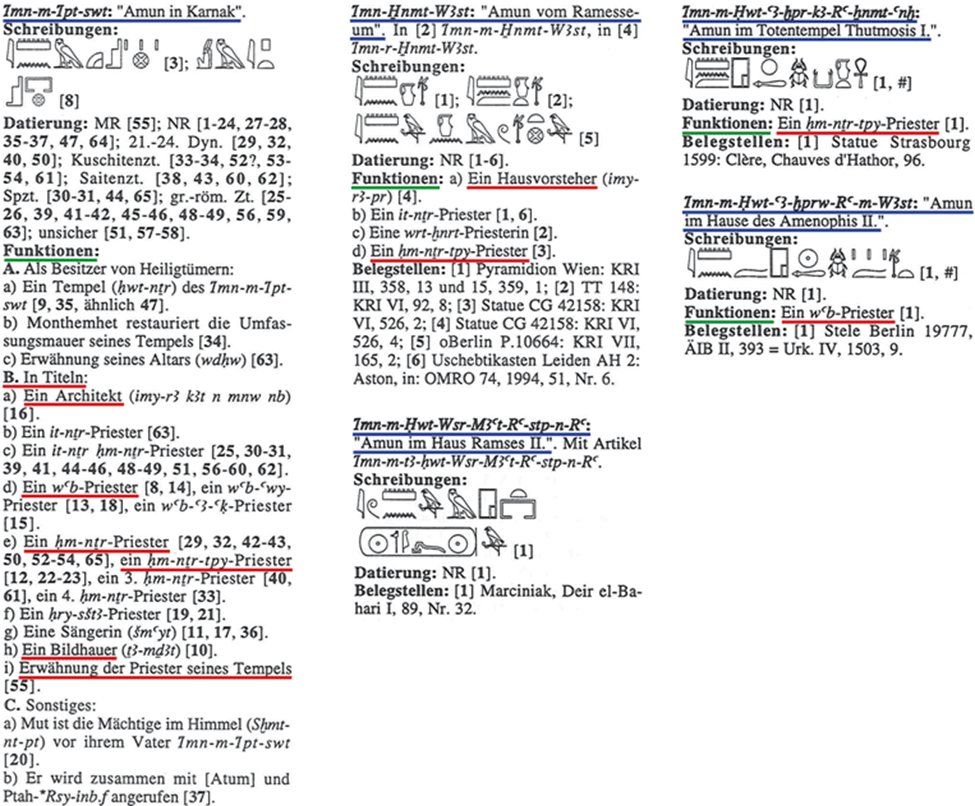

Did the priests of the temple of Amun have Amun’s name as part of their official? Yes. Lexikon Der Ägyptischen Götter Und Götterbezeichnungen under the ancient Egyptian deity "’IMN" lists the following examples.

Figure 6 furnishes us with interesting information concerning the usage of the name ’IMN and shows it had various functions, including use in the titles [‘In Titeln’] of different grades of priestly class – from the lowest wʿb priest [‘Ein wʿb-Priester’] to ḥm-ntr-tpy, i.e., the High Priest [‘Ein ḥm-ntr-tpy-Priester’]. Interestingly, it also cites an example of ’IMN being used in the title for an architect [‘Ein Architekt’], a sculptor [‘Ein Bildhauer’] and a singer [‘Ein Sängerin’]. These categories of people may have been associated with the deity ’IMN through construction and singing hymns in the temple of Amun. For example, consider the entry ‘Amun vom Ramesseum’ or ‘Amun from the Ramesseum (= the mortuary temple of Ramesses II)’ which refers to the title of the High Priest [‘Ein ḥm-ntr-tpy-Priester’] and the Overseer of the House [‘Ein Hausvorsteher’], i.e., the Ramesseum.

The question now is whether ’IMN is in some way related to Haman? For this we have to go into the phonology and lexicography of ’IMN.

How was ’IMN articulated or pronounced? Carsten Peust writing in his book Egyptian Phonology - An Introduction To The Phonology Of A Dead Language indicates there is some debate about its value. See the supporting evidence for full details but to summarize, it can be said that ’IMN may have been pronounced as amana. And as well as ’IMN being mentioned as amana, depending upon the scribe, it is also attested as amanu, amaanu and other variants in cuneiform inscriptions from the New Kingdom Period.[186]

Before we go any further, a few words need to be spoken about the priests and the nature of priesthood in ancient Egypt.[187] The priests in ancient Egypt were religious and temple attendants whose role remained almost the same in all historical periods, i.e., they kept the temple and surrounding sanctuary pure, conducted the cultic rituals and observances, and performed the great festival ceremonies for the public. The priesthood hierarchy had the Pharaoh as chief priest of every cult, and in theory, he had the privilege of attending the deity. In practice, however, since the Pharaoh can’t be present everywhere, the authority was delegated to the High Priest (i.e., the ‘First Prophet’), who was supported by lesser ranked priests who would have attended to offerings and minor parts of the temple ritual. The ‘Second Prophet’, one rank below the ‘First Prophet’, attended to much of the economic organization of the temple, while lower ranks, known as wʿb priests, attended to numerous other duties. The High Priest or the ‘First Prophet’ could wield significant power, and this position allowed him great influence even in secular matters involving medicine, construction, etc. In most periods, the priests of ancient Egypt were members of a family long connected to a particular cult or temple. Priests recruited new members from among their own clans, generation after generation.

The priests conducted the cultic liturgy throughout Egypt as the image of the king and the gods.[188] John Gee has extensively studied this:

In some of the statements of authority, the officiant states his earthly offices that allow him to perform the ritual, in others he takes on not only the attributes of his god but his persona as well, thus becoming that god's literal representative in the ritual.

Thus we have various statements of authority from priests where they not only assume the attributes of various deities but also the persona such as – “I am Horus, who is over heaven, the beautiful one of dread, lord of awe, great of dread, lofty of feathers, chief in Abydos”, “I am Thoth the protector of your bones”, “I am the effective living soul who is in Heracleopolis, who gives offerings and who subdues evil”, etc.[190] Likewise, in the funerary rituals, the priestly impersonators of Anubis – the most important Egyptian funerary god[191] – regularly appear in funerary ceremonies and are styled simply “Anubis”, “Anubis-men”, “I am Anubis”, etc. The priests who impersonate Anubis are seen donning the jackal-headed masks of Anubis while doing the preparation of the mummy and the burial rites.[192] In similar fashion, the High Priest of Amun wore the ram’s skin when impersonating Amun.[193] In fact, this was such a common practice and many more examples can be seen in Lexikon Der Ägyptischen Götter Und Götterbezeichnungen under the listing of various ancient Egyptian deities.[194] One should remember that our understanding of how ancient Egyptians actually understood these ritual practices is not perfect and is subject to interpretation. Shaw summarises the discussion neatly:

Among the many questions that Egyptologists have had difficulties in answering effectively are the following. Did Egyptians actually imagine their deities to exist in the ‘real world’ as hybrids of human and non-human characteristics, from the surprisingly plausibly rendition of the god Horus as a falcon-headed man to the rather less convincing (to our eyes) representation of the sun-god Khepri as a man whose head is entirely substituted by a scarab beetle? Or did they simply create these images as elaborate symbols and metaphors representing the characteristics or personalities of their deities? When we are shown a jackal-headed figure embalming the body of the deceased are we supposed to believe that Anubis, the god of the underworld, was actually responsible for all mummifications or are we being shown a priest-embalmer wearing a mask allowing him to impersonate the god (and if so was he then regarded as actually becoming the god or simply imitating him during the ritual)? There is one surviving full-size pottery mask in the form of Anubis’s jackal head (now in the Pelizaeus Museum, Hildesheim) but this does not really solve the above series of problems. Part of the urgency with which Egyptologists tend to attack such questions probably derives from our desire to find out whether the systems of thought of ancient Egypt were fundamentally different to our own, or whether they just appear so because they are expressed in ways that are now very difficult to interpret.

We have seen that the Pharaoh was both the bodily heir of the creator and his ‘living image’ on earth. Was this aspect of royal divinity also attributed to the liturgical performer (i.e., the High Priest), at least during the performance of the rite? Yes. The ‘royal attributes’ of the High Priest Herihor are perhaps an elaborate development of such a notion. Herihor was the High Priest of Amun who lived in the early period of the 20th Dynasty.[196] He became so powerful that he was in effect the de facto ruler of Thebes. He was portrayed wearing the double crowns of Egypt, something which was exclusively reserved for Pharaohs. At some point during his rule:

Herihor began to insist that the god Amun was advising him on matters of the state and that as a priest of Amun he was favored by the god as the ruler of both Upper and Lower Egypt.

The High Priestdom had ceased to be primarily a religious office and had acquired considerable temporal authority, i.e., rulership, including the generalship of the armies. In other words, the period of the rule of Herihor shows an elaborate development of a High Priest taking the persona of royal divinity.

Let us now test the assumption Haman was a person of importance using the evidence from ancient Egypt.

In our previous study, it was noted that, unlike the Bible, the Qur’an mentions that there was only one Pharaoh during the time of Moses. Our analysis suggested that it was Pharaoh Ramesses II. Within his reign, Moses was born and prophethood was bestowed on him at the age of 40 years. Adding to this the minimum of 8-10 years of Moses’ stay in Midian, we have accounted for 48-50 years of the Pharaoh’s reign. However, there is still those period of times relating to Moses which are unaccounted for.

The events surrounding the conferment of wisdom and knowledge and Moses’ killing of the Egyptian in the Qur’an are mentioned successively, suggesting that they were perhaps separated by a shorter period of time [Qur’an 28:14-22]. Currently, this period of time is unknown. This should not discourage us in the quest for locating the Haman of the Qur’an, for we know the fact that the clash of Moses with Pharaoh, Haman and their supporters truly began only in the former’s second sojourn in Egypt. In other words, following the identification suggested in our previous study, at least 48 regnal years of Ramesses II must have passed before the confrontation between Moses and Pharaoh and his followers. Therefore, it is appropriate to search for Haman of the Qur’an post-Year 48 of the reign of Ramesses II [Figure 7].

Combining the data of ’IMN from ancient Egypt with information from the Qur’an, we now ask whether a priest from ancient Egypt could have been involved in construction as well? Figure 7 gives a chronological chart of High Priests of various gods of ancient Egypt during the reign of Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE). It is clear that only the High Priests Bakenkhons, Prehotep (Jr.), Khaemwaset, Neferronpet, Wennufer (son of Mery), Hori (son of Wennufer), Minmose and Anhurmose reigned post-Year 48 of Ramesses II. The question now is which of these High Priests were involved in construction and served the deity Amun? This information can be obtained from Professor Kitchen’s book series Ramesside Inscriptions and biographical dictionaries of ancient Egypt and is tabulated in Table I.

| Name of the High Priest | Deity Served | Chief / Superintendent / Overseer of Works / Workers |

| Bakenkhons | Amun | Yes. “Chief of Works”, “Overseer of Works”.[199] |

| Prehotep, Jr. | Re and Ptah | Yes. “Chief of Works”.[200] |

| Khaemwaset | Ptah | No. Restored older monuments. High Priest of Ptah and hence the title “Chief of Artificers”.[201] |

| Neferronpet | Ptah | No. High Priest of Ptah and hence the title “Chief Controller of Artificers”.[202] |

| Wennufer (son of Mery) | Osiris | No.[203] |

| Hori (son of Wennufer) | Osiris | No.[204] |

| Minmose | Anhur-Shu | No.[205] |

| Anhurmose | Anhur-Shu | No.[206] |

From the above table it is clear that only the High Priests Bakenkhons (or Bakenkhonsu) and Prehotep, Jr. (also called Prehotep B or Rahotep in scholarly literature) had the title of “Chief of Works”. However, although Prehotep, Jr. held this title, there is no inscription from him mentioning what kind of construction work he did for the Pharaoh. This may be because Prehotep, Jr., apart from holding the High Priesthoods of both Re and Ptah at Heliopolis and Memphis, was also one of the viziers of Ramesses II.[207] His busy schedule probably did not give him enough time to perform extensive duties involving construction, but it is entirely possible that he was involved in maintenance of the temples of Re and Ptah. That leaves us with Bakenkhons, the High Priest of Amun (i.e., ḥm-ntr tp n ’imn).

Bakenkhons was one of the great architects of ancient Egypt.[208] He is well-known for supervising the construction of the temple of Amun at Karnak for Ramesses II. Called by the Egyptians ipet-isut (‘most select of places’), this temple remains the largest religious structure ever created and consisted of a vast enclosure containing Amun’s own temple, as well as several subsidiary temples of other gods”.[209] Such a large scale construction is not surprising at all. The cult of Amun grew in importance and wealth with the elevation of Amun to the position of chief god of Egypt during 18th Dynasty (with a short downturn during the Amarna Period, i.e., in the reign of Akhenaten (or Amenhotep IV, r. 1353-1336 BCE), and the extensive endowments bestowed upon the temple by various rulers.[210] The Ramesside era saw the unprecedented growth of the cult of Amun - the patron god of the state. The flow of wealth and royal patronage of Amun resulted in the growth and relative autonomy of the major temples as well as the power of the High Priests running them, including that of Bakenkhons. However, not all ‘Chiefs of Works / Builders / Architects’ during the time of Ramesses II were High Priests. For example, Penre, Amenemone (alt. sp. Ameneminet), Paser, Maya, Minemhab, Amenmose and Nebnakht, who were not High Priests, also enjoyed one of these aforementioned titles.[211] We have not considered them here because of the fact we are searching for someone who the Pharaoh would entrust the construction of a building with apparently great spiritual significance to, a religiously motivated challenge to Moses and his God. As noted earlier, the Pharaoh’s need for a structure he could climb to the heavens was theological in nature, and so it would seem appropriate that he would assign his chief religious advisor with this task. In other words, Amun being the patron deity of Ramesses II, it would seem likely for the Pharaoh to ask Bakenkhons, who was the High Priest of Amun as well as “Chief of Works”, to construct this.

A few words need to be said about the life of Bakenkhons before delving into the evidence from the Qur’an and comparing it with what we know. Bakenkhons was born c. 1310 BCE.[212] Much of the information about Bakenkhons is gathered from his lengthy biography inscribed on a block statue, now in the Munich Museum – describing the course of his career, from its relatively modest beginnings to one of the most august offices in the land.[213] By the time Bakenkhons died he had been a priest for ~70 years and served Ramesses II throughout his reign. In the last year of Ramesses II’s reign, Bakenkhons died at an age of about 90 years.[214] This is approximately the same age Ramesses II died at (~90-92 years).[215] In other words, both Ramesses II and Bakenkhons were contemporaries who were born and died around the same time.

Now what do we know about Haman in the Qur’an and how does this data fit with what we know from the life of Bakenkhons from ancient Egyptian sources?

As for points §1 and §3, the person of Bakenkhons fits very well. He was the High Priest of Amun, a very senior and influential position, and served the Pharaoh Ramesses II dutifully as he says in his inscription.

The Noble and Count, High Priest of Amun Bakenkhons, justified. He says: ‘I am one truly reliable, useful to his lord, who reveres the fame of his god, who goes (always) upon his way, who performs beneficent deeds within his temple, I being principal Chief of Works in the Estate of Amun, as an efficient confidant of his lord.’

We also learn that Bakenkhons was the ‘Chiefs of Works’ (above cf. §2) and, as gathered from the Munich inscription:

I performed benefactions in the domain of Amun, being overseer of works for my lord. I made a temple for him, (called) “Ramesses-Meryamun-who-hears-prayers” in the upper portal of the domain of Amun. And I erected obelisks of granite in it, whose tops approached the sky, a stone terrace before it, in front of Thebes, the bah-land and gardens planted with trees.

These are two obelisks of Ramesses II at the Luxor Temple, of which one is still in situ [Figure 8], and the other in the Place de la Concorde, Paris.[219] The former obelisk has a height of 82 feet (or 25 meters). The principal entrance of the Luxor Temple is the Pylon of Ramesses II [Figure 8], which is flanked by two colossal seated statues of the Pharaoh (one is behind the obelisk) and one standing statue (of an original four). The height of the pylon is 24 meters, which is close to the height of the surviving obelisk. The walls of the pylon are embellished with records of Ramesses II’s military campaigns and dedicatory inscriptions, among other things. Two of these inscriptions praise the erection of the pylons by saying that its flagstaves reached the heavens.

Dedications on the Pylon (below Cornices)

North (front) Façades.

W. Wing: Horus, Strong Bull, son of Amūn; Two-ladies, the Favourite, [beneficial to his father; Golden Horus, Seeker of good deed]s for him who produced him; King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usimarēʿ-Setepenrēʿ: he has made as his monument for his father Amenresonter the constructing for him of the Temple of Ramesses II Meryamūn in the Domain of Amūn, in front of Southern Opet, and the erecting for him of a pylon anew, its flagstaves reaching up to heaven – being what the Son of Rēʿ, Ramesses II Meryamūn, given life forever, made for him.

....

South (rear) Façades.

W. Wing, upper line: <Horus>, Strong Bull beloved of Maʿat; Two-ladies, Protector of Egypt, who curbs the foreign lands; Golden Horus, Rich in years, great in victories; King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Usimarēʿ-Setepenrēʿ: he has made as his monument for his father Amenrēʿ, presiding over his harim, the constructing for him of a great and noble pylon before his temple, its flagstaves reaching up to heaven, (made of) cedar of God's Land, which the Son of Rēʿ, Ramesses II Meryamūn, given life like Rēʿ forever, has made for him.

Comparing Figure 8 with the phrases in the inscriptions ‘obelisk of granite... whose tops (or beauty) approached the sky’ or ‘its flagstaves reaching up to heaven’ give a good idea as to what is meant. It simply denotes a tall (and beautiful) obelisk or pylon containing flagstaves that were close to 25 meters high. Therefore, it would not be surprising if the Pharaoh had asked one of his ‘Chiefs of Works’, Bakenkhons in our case, with experience in constructing structures ‘whose tops (or beauty) approached the sky (or heaven)’, to build him a lofty palace, so that ‘he may attain the ways and means - The ways and means of (reaching) the heavens’, and that he may ‘mount up to the god of Moses’ [Qur’an 40:36-37].

As for the death of Haman (above cf. §4), opinions differ. Some opine that Haman was drowned while chasing the Children of Israel, while others are silent. The evidence from the Qur’an suggests that Haman might have met with a violent death, as suggested by the verses below.

[Qur'an 29:38-40]

If we look at the explicit mention of the mode of deaths in the Qur’an, we find that the people of ʿAd died by a wind storm [Qur’an 69:6-7], the people of Thamud perished in a mighty blast (an earthquake) [Qur’an 54:31], Qarun was swallowed by the earth [Qur’an 28:81] and the Pharaoh died by drowning [Qur’an 10:90-92]. That leaves only Haman whose mode of death is not explicitly mentioned in the Book. Interestingly, ʿAd, Thamud and Haman are mentioned in connection with extravagant buildings. Could it be possible that Haman died either by a wind storm or an earthquake? There are no certain answers. However, in the case of Bakenkhons we know that he and Ramesses II died close to each other. Before his own death, Ramesses appointed Bakenkhons’ son Roma-Roy as High Priest in his place.

We are now left with some linguistic issues which may connect ancient Egyptian ’IMN (i.e., amana) with Qur’anic Haman (or hmn, if we consider only the consonants). See the supporting evidence for more details, but to summarize, the name of the ancient Egyptian deity ’IMN (or amana) was used in the title for a High Priest as well as an architect. The position of High Priest of Amun was of great importance and influence in ancient Egypt. Combining this data with that present in the Qur’an suggests that Haman may be simply an Arabized version of the ancient Egyptian amana. Barring certain uncertainties such as the mode and time of his death, the life and works of Bakenkhons, the High Priest of Amun, appears to accord well with the data about Haman in the Qur’an. Since events in the distant past can be expressed in a probabilistic manner due to underlying uncertainties, one can say, given the evidence presented above, that Bakenkhons is a good candidate for Haman in the Qur’an.

Another interesting detail which the Qur'an mentions is the day of encounter between Moses and the magicians.

"Then we will surely bring you magic like it, so make between us and you an appointment, which we will not fail to keep and neither will you, in a place assigned." [Moses] said, "Your appointment is on the day of the festival when the people assemble at mid-morning."

SURAH 20 , VERSE 58-59

This is called yaum al-zīna. Zīna means a thing with which or by which one is adorned, ornamented, decorated, etc. So, the phrase yaum al-zīna can mean a day when people are dressed up smartly, or the city is adorned or perhaps both. It could even mean a day of pompous celebration or more precisely a day of festival. Could it refer to the Heb-Sed (or simply Sed) festival? The Heb-Sed Festival, also called a jubilee, was usually celebrated 30 years after a king's rule and thereafter, every three years. Ramesses II celebrated a record 11 or 12 of these after his Heb-Sed festival in year 30. It was to renew the potency of the Pharaoh and to assure a long reign in the afterlife. One of the most important aspects of this festival is that it was probably witnessed by ordinary citizens only very rarely.

"The story of a little girl, Jihad, facing discrimination because of the name her parents gave her.

Pierce the veil--Unlock the truth--Racism, Nationalism, & Islamophobia, examined through the unbiased lens of scientific inquiry."